InnoDB Buffer Pool LRU Implementation: How MySQL Optimizes Memory Management

InnoDB Buffer Pool LRU Implementation

While reading the InnoDB Storage Engine documentation, I found that it uses a variant of LRU eviction to manage its cache.

At a high level, the storage engine structures can be divided into:

-

On-disk structures:

These are the physical files that persist your data, including tablespaces (likeibdata1or per-table.ibdfiles), redo logs, and undo logs. Since disk I/O is significantly slower than memory access, minimizing trips to these files is one of the primary goals of the engine. -

In-memory structures:

This is where the buffer pool lives. It is an area in main memory where InnoDB caches table and index pages as they are accessed. By keeping frequently accessed data in RAM, InnoDB can process queries much faster. On dedicated database servers, it’s common practice to allocate up to 80% of physical memory to this pool.

The buffer pool uses a variant of the LRU algorithm. It’s implemented as a linked list of pages, where each page is typically 16KB and can hold multiple rows (or index entries).

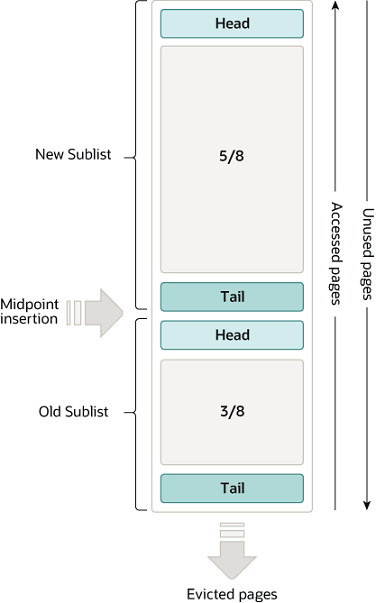

Instead of a single LRU list, InnoDB splits it into two logical parts:

- A “new” sublist for pages that are considered hot / frequently used. The top ~5/8 of the list is the new sublist.

- An “old” sublist for pages that have been seen recently but are not yet proven to be hot. The bottom ~3/8 of the list is the old sublist.

Newly read pages are not put directly at the very head of the list. Instead:

- When a page is read into the buffer pool, it is inserted at the head of the old sublist, i.e., at the midpoint of the LRU list (around 3/8 from the tail).

- Only if that page is accessed again (and meets some timing rules) is it promoted into the new sublist and moved toward the real head.

As the database runs:

- Every time a page becomes “new” and is moved toward the head, other pages effectively age and drift toward the tail.

- Pages in the old sublist age both because new/young pages are added above them, and because new pages are continuously inserted at the midpoint.

Eventually, if a page is not accessed for long enough, it reaches the tail of the old sublist and is chosen for eviction when InnoDB needs to free up space in the buffer pool.

The larger the buffer pool, the more InnoDB behaves like an in-memory database i.e. data is read from disk once and then reused from memory on subsequent accesses.

How InnoDB Handles Full Table Scans

Problem with a naive LRU

In a simple LRU design, a full table scan would read a huge number of pages and insert each one at the head of the LRU list. This would push out genuinely hot pages that the workload depends on, effectively trashing the cache.

What InnoDB does instead

-

New pages go into the old sublist first

When a page is read (including during a full table scan), it’s inserted at the head of the old sublist, not directly at the head of the entire LRU. This means the scan populates primarily the old portion of the LRU, which acts as a “quarantine” area. -

Limited size for the old sublist

Only about 3/8 of the LRU is allocated to the old sublist by default (controlled byinnodb_old_blocks_pct).

Even if a full table scan streams in a large number of pages, it mostly churns within this old region, leaving the new sublist (top ~5/8)—where the real working set lives largely intact. -

Delayed promotion of scanned pages

A page is not promoted to the new sublist on the very first touch.

InnoDB can further control promotion viainnodb_old_blocks_time: after a page is first read into the old sublist, it must stay there for at least this configured time before a subsequent access will promote it to the new sublist.

For a single-pass full table scan, most pages are read once and never touched again (or touched again too soon), so they never become “new”. -

Quick eviction of scan pages

Because scan pages live in the old sublist and are rarely reused, they age out quickly and reach the tail of the old sublist.

When the buffer pool needs space, these aging scan pages are evicted first, instead of evicting hot pages from the new sublist.

Effectively:

- Full table scans do not blow away the entire buffer pool.

- They primarily occupy and churn the old sublist, while the truly hot working set remains in the new sublist and stays cached.

Sources

- https://dev.mysql.com/doc/refman/9.0/en/innodb-buffer-pool.html

- https://dev.mysql.com/doc/refman/9.0/en/innodb-performance-midpoint_insertion.html