Notes from Crafting Interpreters - Chapter 2 (A Map of the Territory)

I have started reading Crafting Interpreters by Bob Nystrom. This is a book about creating interpreters for a programming language called Lox. I will be taking notes as I read through the book. This is the second chapter of the book.

The parts of a Language

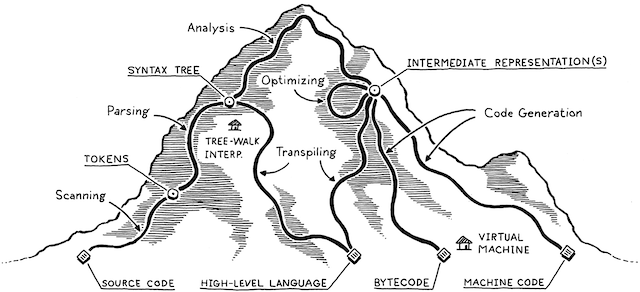

We start of with source code in a high level language. This is just raw text. Each phase in the compiler analyzes the program and transforms it into a different representation. The final objective is to generate machine code that the computer can run.

Source: https://craftinginterpreters.com/a-map-of-the-territory.html

var average = (min + max)/2;

Scanning

First step is scanning, aka lexing or lexical analysis. The scanner takes in the linear stream of characters and chunks

them into meaningful tokens. For example, 123 would be tokenized into a number token. The scanner also removes comments

and whitespace.

+-----+ +--------+ +---+ +---+ +-----+ +---+ +-----+ +---+ +---+ +---+

| var | | average| | = | | ( | | min | | + | | max | | ) | | / | | 2 |

+-----+ +--------+ +---+ +---+ +-----+ +---+ +-----+ +---+ +---+ +---+

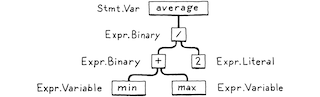

Parsing

This is where our syntax gets a grammar - the ability to compose larger expressions from smaller ones. The parser takes the tokens from the scanner and builds a tree structure called the abstract syntax tree (AST). The AST represents the structure of the program. The parser also checks for syntax errors.

Source: https://craftinginterpreters.com/a-map-of-the-territory.html

Static Analysis

From the previous stages we know the structure of the program. Now we need to check if the program is semantically correct.

For a statement like a+b, we need to check if a and b are defined and if they are of the right type. This is done

by the static analyzer.

Binding or resolution is the process of associating the variable names with their values. This is where scope comes into play. If the language is statically typed, we can also check if the types are correct.

All the semantic insights available need to be stored. There are two ways to do this:

- Decorating the AST: We can add extra information to the nodes in the AST. For example, we can add the type of the variable to the variable node.

- Symbol Table: We can store the information in a separate data structure. This is useful when we need to look up information quickly.

Everything we have done so far is called front end.

Intermediate Representation

The frontend of the pipeline is specific to the source language the program is written in. The backend is concerned with the final architecture where the program will run. The intermediate representation (IR) is the bridge between the two.

The IR is a simplified version of the program that is easier to analyze and optimize. The IR is also independent of the source language and the target architecture. It acts as an interface between the two.

For example, if we wish to run C, Pascal and Fortran code on x86, ARM and MIPS architectures, we can write a compiler for each language that converts the source code to the IR. Then we can write a backend for each architecture that converts the IR to machine code. This way we only need to write 3 frontends and 3 backends instead of 9 compilers.

Optimization

Once we understand the program, we can swap it with a different program that has the same semantics but is faster. This is

called optimization. The optimizer takes the IR and applies a series of transformations to make the program faster.

Example, constant folding and loop unrolling.

penny = 1; nickel = 5; dime = 10; quarter = 25; total = penny + nickel + dime + quarter; can be optimized to total = 41;

for (int i = 0; i < 10; i++) { sum += i; } can be unrolled to sum = 45;

Code Generation

Last step is to convert it to a form the machine can run (primitive assembly-like instructions). We have two options:

- Generate instructions for a real machine, like x86 or ARM. We get an executable that the OS can load directly onto the chip.

- Instead of instructions for a real machine, compiler produce virtual machine code. This is a set of instructions for a hypothetical machine that doesn’t exist. Generally called bytecode because each instruction is often a single byte long.

Virtual Machine

If the compiler generates bytecode, this program cannot be run yet as no chip understands this bytecode. We can either write a little mini-compiler that translates the bytecode to native code for the machine.

Or we can write a virtual machine, that emulates a hypothetical chip supporting the virtual architecture at runtime. Running bytecode on a virtual machine is slower than running native code, but it is more portable.

Runtime

If the compiler generates native code, the program is ready to run. If it generates bytecode, the virtual machine is started and the bytecode is fed to it. The virtual machine is responsible for executing the program. But in both cases, the runtime also provides services like memory management, garbage collection, and exception handling. In a fully compiled language, the runtime is a library that the compiler links into the program.

Shortcuts and Alternate Routes

Not all languages go through all the stages described above.

Single Pass Compilers

Some simple compilers combine scanning, parsing, and static analysis into a single pass. They read the source code from start to finish and generate code as they go. This is faster but less powerful. Since there are no intermediate data structures to store global information, the compiler cannot perform global optimizations. We also do not revisit the code, so when we encounter a function call, we need to know enough to correctly compile it.

For example, we cannot call a function in C above the code that defines it, or we need to declare the function before we call it.

Tree Walk Interpreters

Some programming languages begin executing as soon as the AST is ready after parsing(some static analysis applied). The interpreter traverses the syntax tree one branch and one leaf at a time, evaluating the nodes as it goes. This is called tree walk interpreter.

A tree walking interpreter typically traverses the AST in post order, where the children are evaluated before the parent. For an expression, children are the operands and the parent is the operator. We need to resolve the operands before we can apply the operator.

Transpiler

Transpiler or Trans-compiler compiles a source program in one language to a semantically equivalent program in another language. For example, you write a frontend for your language. Then in the backend, instead of generating machine code, you generate a string of valid source code of some other language. We can then use the compiler for that language to generate the machine code.

One example is TypeScript. TypeScript is a typed superset of JavaScript. TypeScript code is transpiled to JavaScript code before it is run in the browser. A lot of the languages are now transpiled to javascript to be able to run in the browser.

Just-In-Time Compilation

I couldn’t completely wrap my head around JIT based on the explanation in the book. This thread on stackoverflow helped me understand it better: What does a just-in-time (JIT) compiler do?

Compilers and Interpreters

Compiling is translating source code to another low level code (byte code or machine code).

An interpreter takes in a source code and executes it immediately.

Interesting Reads

Do programming language compilers first translate to assembly or directly to machine code?

Interpreters vs Compilers vs Virtual Machines

How does an interpreter/compiler work